Thursday, March 26, 2015

Wednesday, March 25, 2015

Update 6: The End

My genius project is pretty much at an end...I won't consider it "over" until everyone has presented, but I've already given my TEDtalk.

I was super nervous going into it, and I'm not really sure why. Well I know why. I'm a nervous wreck - I get nervous about everything. But I knew I was prepared and I really liked my script going into it, but I think that might have made it worse. I set high expectations for myself and then scared myself into thinking I wouldn't be able to meet them.

I'm not entirely pleased with how it went. I messed up a few times, but for the most part, I felt like I was on autopilot. I was about two thirds of the way done my script, and it felt like I had only been talking for ten seconds. The feedback from my friends was nice, but I've felt confident about other projects before...and the grades have fallen flat.

Anyway, I'm really stressed out right now because of other schoolwork, and I think I'm just making it worse by dwelling on this. I am pleased with how my project turned out, and it's been good motivation for me to continue learning Chinese. After my grandparents return to China, I hope to keep up communication with them in a language they actually understand. I've also really enjoyed watching other people progress through the weeks. Some people have made extraordinary progress, and I'm so so so proud of them :)

If you've kept up with my monstrosity of a blog, thank you so much. Good luck to anyone who's presenting in the next few days, and congrats to those who've finished!

- Jess

I was super nervous going into it, and I'm not really sure why. Well I know why. I'm a nervous wreck - I get nervous about everything. But I knew I was prepared and I really liked my script going into it, but I think that might have made it worse. I set high expectations for myself and then scared myself into thinking I wouldn't be able to meet them.

I'm not entirely pleased with how it went. I messed up a few times, but for the most part, I felt like I was on autopilot. I was about two thirds of the way done my script, and it felt like I had only been talking for ten seconds. The feedback from my friends was nice, but I've felt confident about other projects before...and the grades have fallen flat.

Anyway, I'm really stressed out right now because of other schoolwork, and I think I'm just making it worse by dwelling on this. I am pleased with how my project turned out, and it's been good motivation for me to continue learning Chinese. After my grandparents return to China, I hope to keep up communication with them in a language they actually understand. I've also really enjoyed watching other people progress through the weeks. Some people have made extraordinary progress, and I'm so so so proud of them :)

If you've kept up with my monstrosity of a blog, thank you so much. Good luck to anyone who's presenting in the next few days, and congrats to those who've finished!

- Jess

Sunday, March 22, 2015

Update 5: The End is Nigh

THIS IS GOING TO BE A SUPER FAST POST LIKE SPEED OF LIGHT BECAUSE I HAVE A LOT OF HOMEWORK BUT I STILL WANTED TO WRITE THIS BUT I MIGHT PASS OUT BECAUSE OF ALL I HAVE TO DO THANKS

This weekend has been fairly busy - I was away for most of it kicking butt at Deutschfest (wir gewannen!). But I am back and better before because this is the final update before my TEDtalk ~reflection.

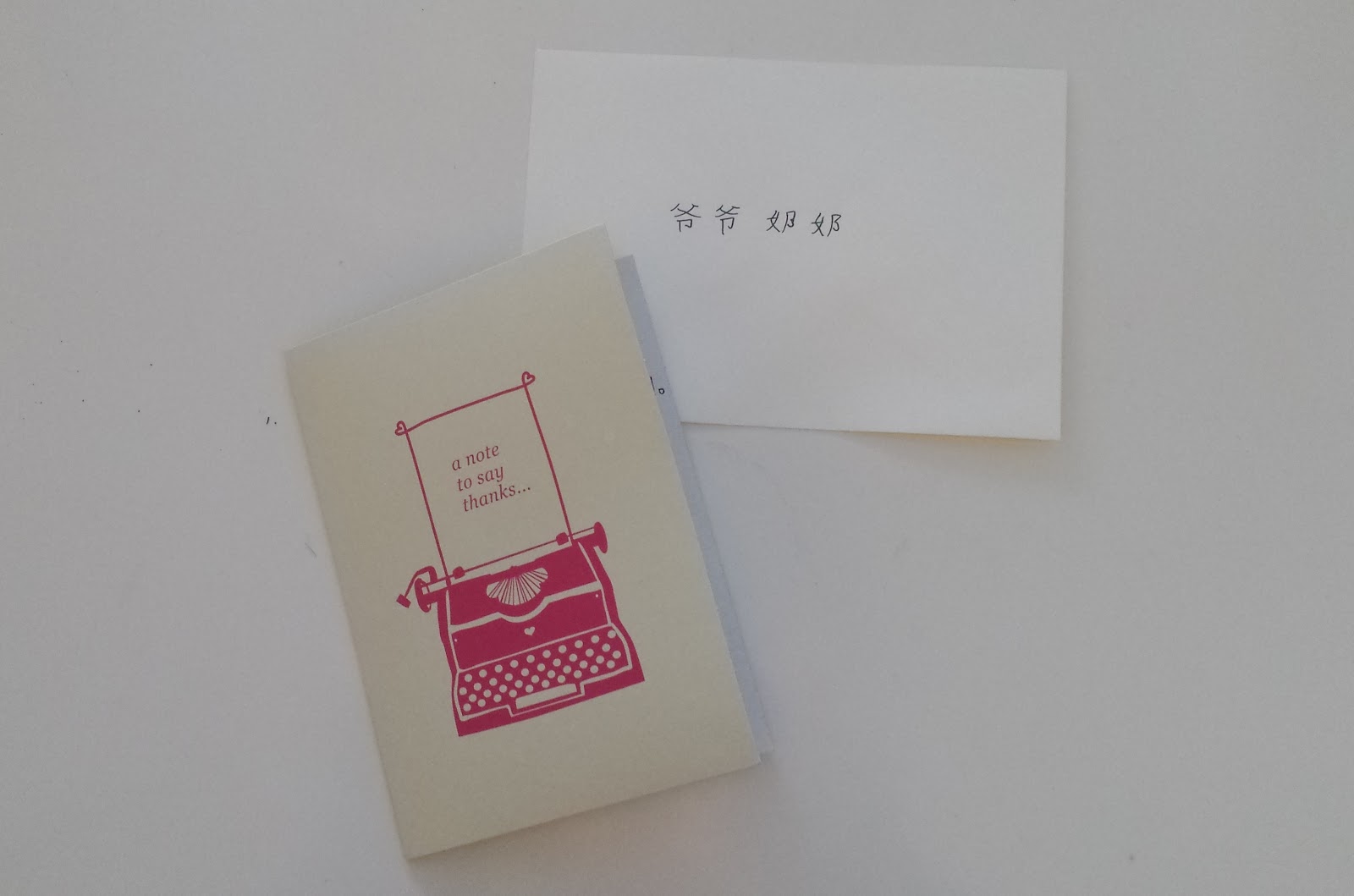

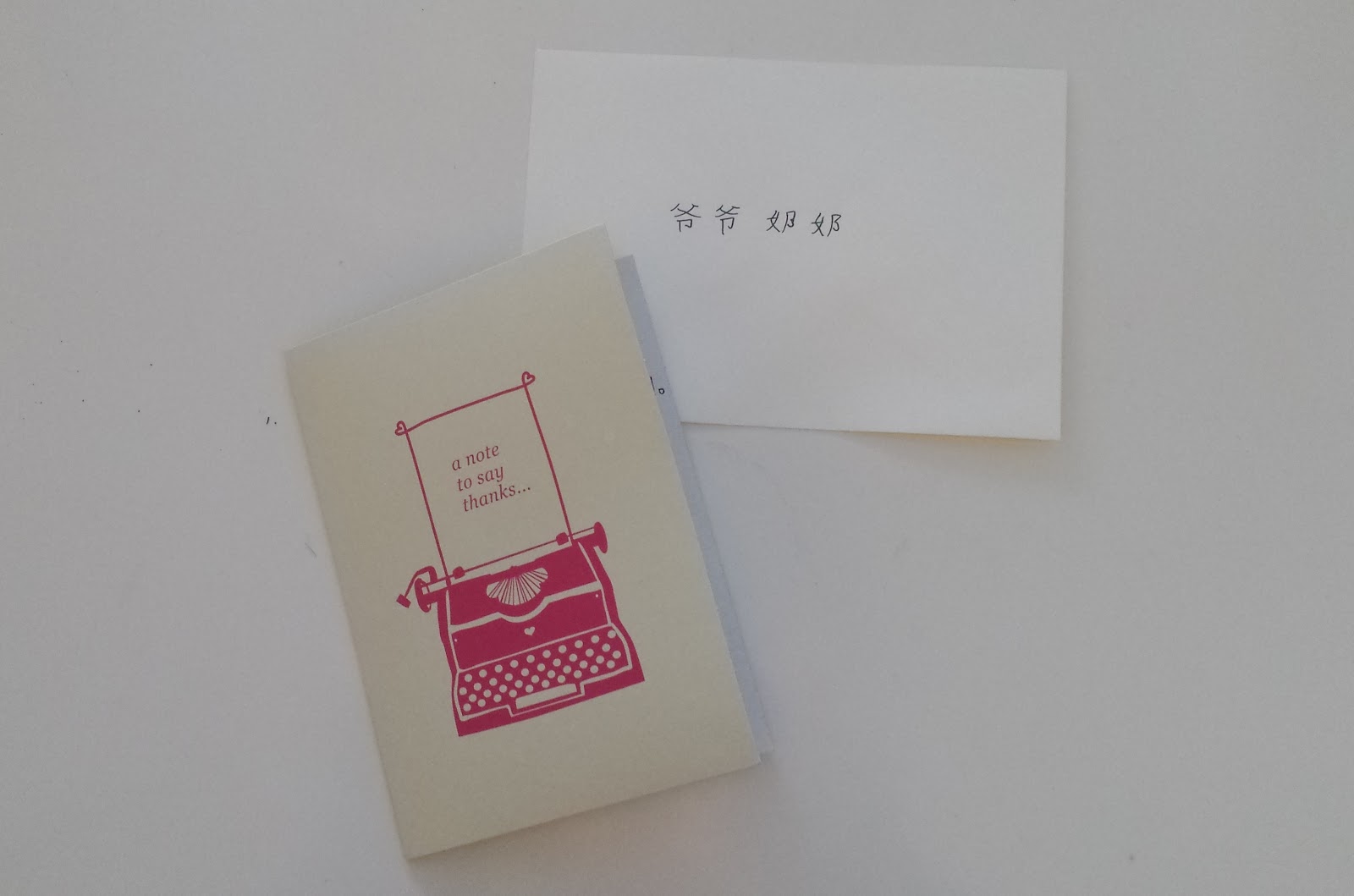

So this week, I decided to forgo writing sentences because I was working on my final product: a thank you card for my grandparents. Here is the card and envelope. It's a bit small, but the envelope says 爷爷奶奶 (yéyé nǎinai) - (paternal) grandfather and (paternal) grandmother. I mentioned in my first post, but the Chinese words for family members are very specific, so the words differentiate between paternal and maternal sides.

So this week, I decided to forgo writing sentences because I was working on my final product: a thank you card for my grandparents. Here is the card and envelope. It's a bit small, but the envelope says 爷爷奶奶 (yéyé nǎinai) - (paternal) grandfather and (paternal) grandmother. I mentioned in my first post, but the Chinese words for family members are very specific, so the words differentiate between paternal and maternal sides.

Anyway, here's the translation:

I said for my last post, I would tell you about the different dialects of Chinese, so here's the super quick condensed version:

If you'd like a more detailed explanation and comparisons, feel free to watch this video

Now I'm off to practice my TEDtalk and drown in my other homework.

- Jess

This weekend has been fairly busy - I was away for most of it kicking butt at Deutschfest (wir gewannen!). But I am back and better before because this is the final update before my TEDtalk ~reflection.

So this week, I decided to forgo writing sentences because I was working on my final product: a thank you card for my grandparents. Here is the card and envelope. It's a bit small, but the envelope says 爷爷奶奶 (yéyé nǎinai) - (paternal) grandfather and (paternal) grandmother. I mentioned in my first post, but the Chinese words for family members are very specific, so the words differentiate between paternal and maternal sides.

So this week, I decided to forgo writing sentences because I was working on my final product: a thank you card for my grandparents. Here is the card and envelope. It's a bit small, but the envelope says 爷爷奶奶 (yéyé nǎinai) - (paternal) grandfather and (paternal) grandmother. I mentioned in my first post, but the Chinese words for family members are very specific, so the words differentiate between paternal and maternal sides.Anyway, here's the translation:

So, after writing that translation, I realized how short that sounds. But while writing this, I was super stressed that I was going to mess up. I'm really happy with the final product - I think this is the neatest I've written any Chinese ever. Like ever. Some of it sounds really awkward because I'm not quite sure how to say exactly what I want...but I think I conveyed the right message. I'm nervous to show my grandparents, but I think they'll appreciate it :)Thank you both. I really like everything you do, like cooking and cleaning. When you leave, my father and I will miss you. I will call and write emails. I love you.

I said for my last post, I would tell you about the different dialects of Chinese, so here's the super quick condensed version:

- There are many, many dialects of Chinese

- "Dialects" isn't really an accurate term - many are not mutually intelligible and are more like independent languages by themselves

- Most dialects are classified into seven groups

- Within these groups, there are most likely smaller, regional dialects

- For example, my family speaks "Shanghainese", which isn't considered a major dialect, but it's very common in Shanghai

- If you're wondering, I can understand Shanghainese, but I can't really speak it

- Mandarin

- Spoken by ~71.5% of the pop

- Spoken in the north and southwest regions of China

- Wu

- Spoken by ~8.5% of the pop

- Spoken in the coastal area around Shanghai and Zhejiang

- Gan

- Spoken by ~2.4% of the pop

- Spoken around the Jiangxi province

- Xiang

- Spoken by ~4.8% of the pop

- Spoken around Hunan

- Hakka

- Spoken by ~3.7% of the pop

- Spoken in scattered areas from Sichuan to Taiwan

- Yue

- Spoken by ~5.0% of the pop

- Spoken around Guangdong and Guangxi, as well as Hong Kong & Taiwan

- Also known as Cantonese

- Min

- Spoken by ~4.1% of the pop

- Spoken in Fujian and coastal regions in the south

- Source

- Jess

Thursday, March 12, 2015

Update 4: Crawling...

There's a Light at the End of the Tunnel...Right?

As I struggle to balance all my homework, this project is the thing that gets neglected. You know how you write a To-Do List, but then you usually leave one or two things unfinished? Yeah...this project is usually that last thing. I'm glad I made my calendar at the beginning of the project because, without it, I'd just be floating in space with no sense of responsibility for a due date. That being said, I may get a few extra days for this project because our snow days pushed things back a bit.

Spread the Love

As usual, I've been continuing with the practice sheets and flashcards. Here's an updated picture of all my flashcards. I don't know how well you can see in the picture, but my stack totals 2.5 inches now! I've mentioned that I've written the German translations on my flashcards, and I realized that I could have a use for these outside my project. I'm going on my school's German exchange this summer, and my partner lived for a while in Hong Kong, so she learned Chinese as well! She mentioned that she's interested in relearning some of the language, so I could bring the flashcards to study with her :)

Below is my practice paragraph this week. I tried something new; I highlighted the new vocabulary I used in blue. I liked doing this to see how I was integrating previous knowledge with my new words.

Translation:

I was also considering my overall progress in the project today. As some of you may know, Liliana (who's making balloon animals) basically sat in class and made balloon animals for everyone, and it was obvious how far she's come since the start. I think of other people's projects, such as Allison, whose paintings are gorgeous, and Hanna, who clearly displays so much passion for her project. I got a bit skeptical of myself because I felt my progress was much slower and less visible. I've reassured myself multiple times that Chinese is a complex, lifelong language, and there's only so much I can hope to learn in six weeks. Nevertheless, I can't help but feel a little left behind, as I'm crawling and other people are making bounds and leaps. In the end, I'm really excited to share the culmination (both my thank you card and my TEDtalk), so I try not to get too bogged down.

Why Would Chinese Ever be Easy?

I've mentioned a couple times before on this blog that Chinese would never be easy. Why would the language system be simple when it could be complicated? With things like stroke order and tones, it's easy to get confused. Well, just this one time (and one time only), Chinese is simple. Obviously, Chinese is written in characters. These characters can range from just one stroke, all the way to fourteen. But believe it or not, the writing system I'm learning is actually the simplified version of Chinese. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the Chinese government decided to simplify the writing system, in an effort to increase literacy. The simplified version is called..."simplified" (amazing) and the older version is called "traditional". Below is a comparison between a few simplified or traditional characters.

There are two changes between the traditional and simplified systems: some characters simply use less strokes (as seen above), and some characters have been combined to be written with just one. Although simplified Chinese has some obvious benefits, some people still prefer the traditional system. Traditional Chinese provides more distinction between different Chinese characters, and knowing the traditional system will allow you to read older writings. Different Chinese-speaking countries may use one system over the other, as you can see in the chart below (it also includes dialects, which will be coming up in next week's post)

As I struggle to balance all my homework, this project is the thing that gets neglected. You know how you write a To-Do List, but then you usually leave one or two things unfinished? Yeah...this project is usually that last thing. I'm glad I made my calendar at the beginning of the project because, without it, I'd just be floating in space with no sense of responsibility for a due date. That being said, I may get a few extra days for this project because our snow days pushed things back a bit.

Spread the Love

|

| 2.5 inches of flashcards! |

Below is my practice paragraph this week. I tried something new; I highlighted the new vocabulary I used in blue. I liked doing this to see how I was integrating previous knowledge with my new words.

Translation:

Today, I am excited. Today is Thursday. My friends are good people. There are people that dance. There are people that can sing songs. They are fifteen and sixteen years old. Such good students! Right now I know two hundred and fifty Chinese words.As you might be able to tell, I chose to do a "journal" type entry for my paragraph this week. I talked about how I felt, as well as my friends. I wanted to talk about all of my friends' projects, but I don't know the vocabulary for that yet. I also mentioned my friends singing; that was in relation to the musical. (Kudos to all who participated - you were awesome!!) Again, the translation sounds awkward (as does the original) because I'm still limited in vocabulary.

|

| Another practice sheets |

Why Would Chinese Ever be Easy?

I've mentioned a couple times before on this blog that Chinese would never be easy. Why would the language system be simple when it could be complicated? With things like stroke order and tones, it's easy to get confused. Well, just this one time (and one time only), Chinese is simple. Obviously, Chinese is written in characters. These characters can range from just one stroke, all the way to fourteen. But believe it or not, the writing system I'm learning is actually the simplified version of Chinese. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the Chinese government decided to simplify the writing system, in an effort to increase literacy. The simplified version is called..."simplified" (amazing) and the older version is called "traditional". Below is a comparison between a few simplified or traditional characters.

|

| Traditional vs. Simplified characters |

My parents are from Shanghai, which is located on mainland China. For this reason, I'm most familiar with Mandarin (also Shanghainese) and the simplified system. Obviously, some characters would be easier to learn than others, but both systems still have their advantages. For foreign language learners, I would recommend learning whichever system applies to their region of interest. For example, if you're a student planning on doing an exchange trip in Hong Kong, it might be better to learn traditional. If you're like me, and your family lives in mainland China and you want to better prepare for a vacation there, you should probably learn simplified Chinese.

The End Is Nigh

With this blog post finished, there are only two more posts I need to do: a final update which will include info on dialects and a reflection after my TEDtalk. I'm excited to share my TEDtalk with the class because I feel very passionate about my topic. I'm so thankful that people have taken the time to read my posts and comment, and I'm looking forward to seeing everyone else's projects as well!

With this blog post finished, there are only two more posts I need to do: a final update which will include info on dialects and a reflection after my TEDtalk. I'm excited to share my TEDtalk with the class because I feel very passionate about my topic. I'm so thankful that people have taken the time to read my posts and comment, and I'm looking forward to seeing everyone else's projects as well!

Shout-out to Liliana, for blessing me with Grumpy. We're a happy family.

I'd like to present to you this week: big fluff and little fluff

- Jess

Resources

The End Is Nigh

With this blog post finished, there are only two more posts I need to do: a final update which will include info on dialects and a reflection after my TEDtalk. I'm excited to share my TEDtalk with the class because I feel very passionate about my topic. I'm so thankful that people have taken the time to read my posts and comment, and I'm looking forward to seeing everyone else's projects as well!

With this blog post finished, there are only two more posts I need to do: a final update which will include info on dialects and a reflection after my TEDtalk. I'm excited to share my TEDtalk with the class because I feel very passionate about my topic. I'm so thankful that people have taken the time to read my posts and comment, and I'm looking forward to seeing everyone else's projects as well!Shout-out to Liliana, for blessing me with Grumpy. We're a happy family.

I'd like to present to you this week: big fluff and little fluff

Resources

Sunday, March 8, 2015

Video Blog: A Test of Endurance

Now comes the time for my video blog entry...

I was very worried going into this because of several reasons: a) I have next to no video recording equipment, b) I have only basic editing software, and c) I hate being in front of a camera. I solved problems a) and b) by lowering my standards and just using a webcam and Windows Movie Maker. It worked out better than I thought it would, so I'm satisfied.

Now, I've endured graphing sine waves in pre-calc, poring over the Thirty Years' War in AP Euro, and listening to Mr. McDaniels in history...turns out watching myself over and over again as I edit is way more painful than all of those things combined. I became hyper-aware of all my weird tics and facial expressions - also does my voice really sound like that?? I got so stressed out during editing that afterwards I felt like I had run two whole feet...which is like really far for me.

Vimeo tells me that my frame rate is a bit low...but it doesn't look exceptionally bad, so let me know if there are unexpected issues.

Password: queenjess

Genius Project vlog from Jess on Vimeo.

P.S. Happy International Women's Day!

I was very worried going into this because of several reasons: a) I have next to no video recording equipment, b) I have only basic editing software, and c) I hate being in front of a camera. I solved problems a) and b) by lowering my standards and just using a webcam and Windows Movie Maker. It worked out better than I thought it would, so I'm satisfied.

Now, I've endured graphing sine waves in pre-calc, poring over the Thirty Years' War in AP Euro, and listening to Mr. McDaniels in history...turns out watching myself over and over again as I edit is way more painful than all of those things combined. I became hyper-aware of all my weird tics and facial expressions - also does my voice really sound like that?? I got so stressed out during editing that afterwards I felt like I had run two whole feet...which is like really far for me.

Vimeo tells me that my frame rate is a bit low...but it doesn't look exceptionally bad, so let me know if there are unexpected issues.

Password: queenjess

Genius Project vlog from Jess on Vimeo.

Thursday, March 5, 2015

Update 3: Outside It's Cold (But Not as Cold as My Heart)

...Snow Day!

I'm currently ensconced in about forty feet of snow, and I'll have two tests tomorrow. So I'm writing this blog post. I'm also feeling very anxious because I'm expecting at least one package in the mail today, and it's probably sitting right in my mailbox...but I can't get to it.

Behind the Scenes

As you may know, the culmination of this project will be a live TEDtalk in front of our gifted classmates. I'm happy to report that I'm on schedule, and I've finished with my script and prezi. Now I'm just off to practice, practice, practice....and practice some more. I've also confused myself a little bit because it seems I planned out about six or seven weeks' worth of learning and blog posts, even though we have a little less than that. Because I'm stubborn as always and determined to get stuff done, I'll probably just do some extra blog posts to make up for it.

Additionally, I said at the beginning of my project that my end goal would be to write a recipe for scallion pancakes in Chinese. I know many of you were looking forward to that (mainly because there was a possibility of scallion pancakes...), but I think I might have to change that :( I really apologize for that, and as you may be able to tell, I like to stick with the goals I set for myself. However, after considering my motivations for this project, I decided it would be best to change my goal. My grandparents are currently staying with me and my father, but they'll be leaving around spring break. They've done a lot for me and my dad while they've been here by cooking and cleaning around the house. I mentioned that I wanted to learn Chinese in order to connect with my family members, so I thought it would be appropriate to write a thank you card for them in Chinese.

Auf Deutsch, Bitte!

Business as usual on the Chinese-learning front - still going through tons of practice sheets and flashcards. I've used up literally all the 3x5 flashcards I have, but luckily, my dad bought me three hundred 5x8 flashcards last year, so I'll use my paper cutter on those.

This past weekend, my family went to Chinatown. I was half-asleep, but then I remembered I could actually read more than three characters in Chinese. I took a look at the signs around the restaurants and shops and...nope. I could recognize a few new characters, but most of them were just unintelligible to me. I said at the beginning of my project that, even by the end, 300 characters would be too little to be "literate" in Chinese. Nevertheless, I'm not discouraged. Below is a shot of one of my practice sheets from this week.

For my practice sentences this week, I decided to change it up. In previous weeks, I've written separate, unrelated sentences. Because my end goal is to actually write something cohesive in Chinese, I thought I would try to write a short paragraph this week. It was definitely out of my comfort zone; it took me a lot longer to write these than in previous weeks. I also mentioned last week that I had trouble with the proportions of my characters. I tried graph paper, but concluded the grid was too small. I decided to create my own lines this week, and I'm happier with the results. The translation is as follows:

You Call My Mother Cow??

This week's info on Chinese is gonna be a doozy. I have three things planned, which means I'll probably end up talking about fifteen. You've seen on my blog that I write the phonetic versions of all my Chinese characters. This is called pinyin in Chinese. Pinyin can be useful because it's a bit easier for people to understand, if they don't see Chinese characters often (like me). However, Chinese speakers would almost never use pinyin to write. With smartphones, people often type the pinyin they want to use, but then select the character. That being said, Chinese people will still recognize pinyin. Like any other languages, there are rules for how to pronounce each vowel, consonant, and different combinations. Because it's fairly complex, I won't explain how everything about pinyin. You can check out this site, if you want to learn more.

Also on this site, you'll find different tones. Chinese is a tonal language; English is not. In tonal languages, the pitch of a speaker's voice can change what word they're saying. (The word for mother (mā) is pretty similar to the word for horse (mǎ). So it's possible a learner would mix up the two!) Consider the following sentence:

Tones can be written with the marks (shown in the image) above vowels. Sometimes, they're also written with a number after the pinyin. For example, mā can be ma1. There are also three tone rules that can change the tone of a character. These rules may not always be reflected in writing, but you will hear them in speaking. The website above also has audio examples of these.

|

| I feel you, bud |

Behind the Scenes

As you may know, the culmination of this project will be a live TEDtalk in front of our gifted classmates. I'm happy to report that I'm on schedule, and I've finished with my script and prezi. Now I'm just off to practice, practice, practice....and practice some more. I've also confused myself a little bit because it seems I planned out about six or seven weeks' worth of learning and blog posts, even though we have a little less than that. Because I'm stubborn as always and determined to get stuff done, I'll probably just do some extra blog posts to make up for it.

Additionally, I said at the beginning of my project that my end goal would be to write a recipe for scallion pancakes in Chinese. I know many of you were looking forward to that (mainly because there was a possibility of scallion pancakes...), but I think I might have to change that :( I really apologize for that, and as you may be able to tell, I like to stick with the goals I set for myself. However, after considering my motivations for this project, I decided it would be best to change my goal. My grandparents are currently staying with me and my father, but they'll be leaving around spring break. They've done a lot for me and my dad while they've been here by cooking and cleaning around the house. I mentioned that I wanted to learn Chinese in order to connect with my family members, so I thought it would be appropriate to write a thank you card for them in Chinese.

|

| My flashcards so far |

Auf Deutsch, Bitte!

Business as usual on the Chinese-learning front - still going through tons of practice sheets and flashcards. I've used up literally all the 3x5 flashcards I have, but luckily, my dad bought me three hundred 5x8 flashcards last year, so I'll use my paper cutter on those.

This past weekend, my family went to Chinatown. I was half-asleep, but then I remembered I could actually read more than three characters in Chinese. I took a look at the signs around the restaurants and shops and...nope. I could recognize a few new characters, but most of them were just unintelligible to me. I said at the beginning of my project that, even by the end, 300 characters would be too little to be "literate" in Chinese. Nevertheless, I'm not discouraged. Below is a shot of one of my practice sheets from this week.

|

| Practice sheet - I'm up to 22 now! |

|

| My practice paragraph |

I speak English. I want to learn Chinese. I use a pen to write words. My Chinese is okay. My friends and my dad all speak Chinese. I love learning. I don't recognize many words.As you can tell, the sentences are a bit awkward and choppy (and that's not just because of the translation). This is partly because I'm limited in vocabulary, but also because I haven't learned some of the conjunctions that would link sentences together. Next week, I'm going to try the same kind of exercise, but I'm going to push myself to try different sentence structures. If you didn't notice, all my sentences were subject-verb-whatever comes after that. As I was writing these, my brain started getting mixed up and I started saying the sentences in German! (It is much easier for me to use German than it is to use Chinese at this point.)

You Call My Mother Cow??

This week's info on Chinese is gonna be a doozy. I have three things planned, which means I'll probably end up talking about fifteen. You've seen on my blog that I write the phonetic versions of all my Chinese characters. This is called pinyin in Chinese. Pinyin can be useful because it's a bit easier for people to understand, if they don't see Chinese characters often (like me). However, Chinese speakers would almost never use pinyin to write. With smartphones, people often type the pinyin they want to use, but then select the character. That being said, Chinese people will still recognize pinyin. Like any other languages, there are rules for how to pronounce each vowel, consonant, and different combinations. Because it's fairly complex, I won't explain how everything about pinyin. You can check out this site, if you want to learn more.

Also on this site, you'll find different tones. Chinese is a tonal language; English is not. In tonal languages, the pitch of a speaker's voice can change what word they're saying. (The word for mother (mā) is pretty similar to the word for horse (mǎ). So it's possible a learner would mix up the two!) Consider the following sentence:

I never said she stole my money.

If you put the emphasis on a different word each time you say the sentence, you change the meaning of the sentence. Emphasis and tonality are not the same thing, but I think it's an easy way to understand how changing the sound of your voice could change the meaning of something.

There are five tones in Chinese; one of these is "neutral". The image below does a good job of demonstrating how tones work: you change both the pitch of your voice, but (this is subtler) you also alter the amount of time you pronounce the word.

- Tone 1

- High pitch

- Level

- Nearly monotone

- Tone 2

- Slight rise in pitch at the end

- Similar to the pitch an English speaker would use to ask a question

- Tone 3

- Pitch falls, then rises again

- The falling-rising sound should be distinctive

- Tone 4

- Pitch starts high, then drops

- Similar to a command in English

- Tone 5/Neutral tone

- Pronounced quickly

- Little regard for pitch

Tones can be written with the marks (shown in the image) above vowels. Sometimes, they're also written with a number after the pinyin. For example, mā can be ma1. There are also three tone rules that can change the tone of a character. These rules may not always be reflected in writing, but you will hear them in speaking. The website above also has audio examples of these.

- 3-3 to 2-3

- If there are two third-tone words in a row, the first word becomes a second-tone word

- 不

- 不 (bù) is a negation word

- Fun fact: Chinese has no direct translation for the word "no" - there are just various words we use to negate certain ideas (kind of like the way English speakers may use "not")

- As you can see above, 不 is typically a fourth-tone word

- If 不 precedes a fourth tone word, it changes to second tone

- 一

- 一 (yī) means "one"

- Typically a first-tone word

- Becomes second-tone when followed by fourth-tone

- Becomes fourth-tone when followed by any other tone

Thanks for reading through this monstrosity. I have two presents for you this week: firstly, check out the YouTube series Adult Wednesday Addams. Every Wednesday, Melissa Hunter uploads a short vignette about Wednesday Addams in typical, adult life.

|

| #me |

And the one you've been waiting for (get on this level, Josh):

3: Weekly Comments

I keep seeing everyone add nice little notes or puns to their comment posts, and mine feel so....blank and heartless....perfect.

Sunday, March 1, 2015

Meanderings: A Quick Note to My Teachers

**If you're not a teacher, you can ignore this.**

Because I like to make things easy for people, I decided to start numbering my updates from 0. That means that "update 1" is really my second update, "update 2" is my third, etc. I just wanted to make sure there wasn't any confusion.

(And no, I'm not just going to change the numberings. Why would I ever do that?)

Because I like to make things easy for people, I decided to start numbering my updates from 0. That means that "update 1" is really my second update, "update 2" is my third, etc. I just wanted to make sure there wasn't any confusion.

(And no, I'm not just going to change the numberings. Why would I ever do that?)

Thursday, February 26, 2015

Update 2: Back to Pre-School

What the Frick-Frack-Paddy-Whack-Diddly-Dack is a Twenty?

I have discovered something truly great about this blog: it's a great way for me to procrastinate, while still feeling like I'm getting something done. And while we're on the topic of my admirable study habits, I'd like to share a story my parents told me when I was younger:

The Struggle is Real

This week's characters were a bit harder than the previous week's - mostly because they're building in difficulty. By difficulty, I mean the obscurity of the word. Not that I'm learning how to write "enigma" or "relentless" in Chinese, but that these characters aren't the most obvious ones that I still remember from Chinese school. In other words, I didn't recognize most of these characters (compared to last week, when I did recognize a good number of them). This was a little challenging, but I employed the help of Dani, who apparently is a lot more creative than I am (honestly, who knew?). I would go through my flashcards with her, and if I was stuck on a word, she would usually help me find some sort of visual cue to help me remember it. For example, I was stuck on the word kè (guest) for a really long time. I eventually realized that the character 客 had a little kǒu (口) on the bottom. This character by itself can mean mouth or opening. And I thought to myself - you would open your home to a guest, so it makes sense that there's an opening in the character for guest. I have no idea if that was intentional, but now I never forget it!

I've also been struggling with proportions. If you've seen my handwriting in real life, you'll know that

I usually don't struggle with making it look nice. That is, when I write in English. Catelyn said to me a little bit before I even knew this would be my genius project, "I bet your handwriting in Chinese would look really nice." Ha. You were so wrong. Sometimes, I write my characters really tiny and compact - a bit more like my handwriting in English. Other times, I write the characters so big they look like a toddler's handwriting. Part of the problem may be that I write on plain paper without any grids or lines. Sometimes, Chinese practice sheets come with little dotted lines within the boxes, so students can write the strokes in the right positions and in proportion. To test my theory, I wrote a few characters on graph paper, which you can see below. It reminded me of the long strips of paper we'd get in elementary school to practice our handwriting - fun fact: I would always get compliments from my elementary school teachers on my handwriting! Anyway, I think the graph paper helped me regulate the overall size, but the grid itself was probably too small for me to write some of the more complicated characters.

Within the characters themselves, I also struggle with proportions. Chinese characters are made of individual little elements. Sometimes, I would write these elements too big or too small in comparison with the others and end up with a really deformed looking character. Speaking of these elements, now would be a good time to introduce what the actual topic of my blog post is about:

That's Totally Radical, Bro

Believe it or not, Chinese radicals are actually automated buttons you can attach to a skateboard, and they say "bruh" every time you do something totally gnarly.

I'm sorry, that's not actually what they are, and the day someone invents that is the day I enter permanent hibernation underneath Earth's crust. Chinese radicals are called 部首 (bù shǒu), literally "section header". Many Chinese dictionaries come with an index for radicals, and the most commonly accepted table includes 214 radicals (again, why would Chinese ever be easy?). You can think of radicals like prefixes or suffixes: they're often attached to or appear on Chinese characters, and they can sometimes hint at the meaning of a character. Radicals can appear on the top, bottom, left, right, or in the middle of characters. They can make learning Chinese simpler, but I wouldn't recommend trying to memorize all of them. You're better off just noticing when they appear and making connections.

I'm not going to try and explain all of these, but I'll show you how they can be used. 艹 is a radical meaning "grass". It appears at the top of characters. Although it means "grass", I think of it more of as "nature" radical. As you can see, it appears in the character for flower 花 (huā), tea 茶 (chá), and the word grass itself 草 (cǎo). Some radicals are more common than others, and some don't really even have meaning - they're just common reoccurring elements. But radicals can be really useful and, to someone learning a pictorial language, they provide a little method to the madness.

Returning to the Struggle

I also need to show you the practice sentences I wrote this week. As I learn more words, I'm getting excited because I can finally express my thoughts on paper, instead of solely verbally.

Some of these sentences are a bit awkward in Chinese because I haven't learned how to write some of the nonsense phrases that make things sound more natural. For now, I'm trying to use new vocabulary, but also mix in words that I learned last week.

Also, I should tell you that, on my flashcards, I've been putting the pinyin (phonetic version of the characters, coming later in a blog post) and German translations of the word. Usually, I can recognize the character with just the pinyin, but I like putting the German to exercise all my language skills. Interestingly, I had the word 宿 (sù) this week. It means "to stay overnight". Obviously, we don't have a single-word English translation for this....but the German verb übernachten is a perfect translation. Funny how languages work, right?

There is one more thing I want to show you (before we get to the cute animals...): Chinese cursive! Most people only use cursive as a sort of shorthand, or just for aesthetic design purposes. I know I'm not exactly literate in Chinese, but I can hardly read it. Imagine your doctor writing in that!

As promised, here's your cute animal of the week.

- Jess

Resources

I have discovered something truly great about this blog: it's a great way for me to procrastinate, while still feeling like I'm getting something done. And while we're on the topic of my admirable study habits, I'd like to share a story my parents told me when I was younger:

This week's practice characters included the numbers one through ten, which I luckily already knew. The nice thing about Chinese numbers is that, once you know one through ten, you know all of them! Here's how it works: numbers larger than ten are kind of like "compounds". You break them up into the different parts of the number. For example, the number twenty-three is 二十三 - both written and pronounced "two ten three". Once you get to 100 and larger numbers, you use different characters (they're not based around ten anymore), but this makes Chinese counting a lot simpler than English (how are we supposed to know that "twenty" is two tens??). Malcolm Gladwell actually proposes in his book Outliers that the simplicity is part of the reason why Chinese students score so well on math tests - because they have an easier time counting in early childhood.One day, a boy went to school. There at school, the students were learning how to write numbers. The teacher started with the character for one (yī). It is, as you will observe, a single line: 一. Then, the teacher moved on to two (èr). It was two lines: 二. Next, the teacher taught them how to write three (sān). As the boy predicted, it was three lines: 三. After seeing this, the boy got up and said, "Well, I know how to write numbers now!" And promptly went home. After staying out of school, for a few days, the boy decided to return. That day, the students were taking a test on how to write numbers. The boy thought it would be easy - until the teacher asked them to write "one thousand" in Chinese!

Chinese numbers 0-9

The Struggle is Real

This week's characters were a bit harder than the previous week's - mostly because they're building in difficulty. By difficulty, I mean the obscurity of the word. Not that I'm learning how to write "enigma" or "relentless" in Chinese, but that these characters aren't the most obvious ones that I still remember from Chinese school. In other words, I didn't recognize most of these characters (compared to last week, when I did recognize a good number of them). This was a little challenging, but I employed the help of Dani, who apparently is a lot more creative than I am (honestly, who knew?). I would go through my flashcards with her, and if I was stuck on a word, she would usually help me find some sort of visual cue to help me remember it. For example, I was stuck on the word kè (guest) for a really long time. I eventually realized that the character 客 had a little kǒu (口) on the bottom. This character by itself can mean mouth or opening. And I thought to myself - you would open your home to a guest, so it makes sense that there's an opening in the character for guest. I have no idea if that was intentional, but now I never forget it!

I've also been struggling with proportions. If you've seen my handwriting in real life, you'll know that

|

| Some grids for Chinese practice |

|

| Practicing on graph paper |

That's Totally Radical, Bro

Believe it or not, Chinese radicals are actually automated buttons you can attach to a skateboard, and they say "bruh" every time you do something totally gnarly.

I'm sorry, that's not actually what they are, and the day someone invents that is the day I enter permanent hibernation underneath Earth's crust. Chinese radicals are called 部首 (bù shǒu), literally "section header". Many Chinese dictionaries come with an index for radicals, and the most commonly accepted table includes 214 radicals (again, why would Chinese ever be easy?). You can think of radicals like prefixes or suffixes: they're often attached to or appear on Chinese characters, and they can sometimes hint at the meaning of a character. Radicals can appear on the top, bottom, left, right, or in the middle of characters. They can make learning Chinese simpler, but I wouldn't recommend trying to memorize all of them. You're better off just noticing when they appear and making connections.

|

| If you've ever had nightmares about verb tables, this is way scarier. For definitions, check out this website |

Returning to the Struggle

I also need to show you the practice sentences I wrote this week. As I learn more words, I'm getting excited because I can finally express my thoughts on paper, instead of solely verbally.

- Girls learn English.

- Your name is...

- I sit on the ground.

- He lives in the courtyard.

- Your child is a foreigner. (Note: "foreigner" has some negative/insulting connotations in English; this isn't the case in Chinese.)

- I ask you.

- This painting is very expensive.

Some of these sentences are a bit awkward in Chinese because I haven't learned how to write some of the nonsense phrases that make things sound more natural. For now, I'm trying to use new vocabulary, but also mix in words that I learned last week.

Also, I should tell you that, on my flashcards, I've been putting the pinyin (phonetic version of the characters, coming later in a blog post) and German translations of the word. Usually, I can recognize the character with just the pinyin, but I like putting the German to exercise all my language skills. Interestingly, I had the word 宿 (sù) this week. It means "to stay overnight". Obviously, we don't have a single-word English translation for this....but the German verb übernachten is a perfect translation. Funny how languages work, right?

There is one more thing I want to show you (before we get to the cute animals...): Chinese cursive! Most people only use cursive as a sort of shorthand, or just for aesthetic design purposes. I know I'm not exactly literate in Chinese, but I can hardly read it. Imagine your doctor writing in that!

|

| Regular writing (left) vs. Cursive (right) |

- Jess

Resources

Wednesday, February 18, 2015

Meanderings: 新年快乐!

Hello, readers!

As you may have noticed, my blog posts are usually rather lengthy...that's because I have a lot of ideas throughout the week, and I save them up to write in one cumulative blog post. I've seen some of my friends do these types of posts, so I'm going to start a specific category for all my rambling, slightly off-topic, meandering thoughts. (Honestly, I'm so clever. I'm like...a Renaissance man...)

If you can read the title, you may have already guessed what this post is about. Chinese New Year starts tomorrow! This year is the year of the sheep (羊). I say "starts" because Chinese New Year is a large celebration in China, lasting about two weeks. People get time off from work and school to celebrate with their families. In fact, some call this time of year the world's largest "human migration" because so many people take public transportation or fly home to celebrate. You may also lion parades at the beginning of Chinese New Year, and a televised event, the New Year's Gala, similar to the United States' Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve (what a mouthful). On the whole, Chinese New Year is usually a much bigger celebration than the regular calendar New Year. Families, government officials, stores, airlines, and more all build up to the holiday with decorations, speeches, and special merchandise.

If you can read the title, you may have already guessed what this post is about. Chinese New Year starts tomorrow! This year is the year of the sheep (羊). I say "starts" because Chinese New Year is a large celebration in China, lasting about two weeks. People get time off from work and school to celebrate with their families. In fact, some call this time of year the world's largest "human migration" because so many people take public transportation or fly home to celebrate. You may also lion parades at the beginning of Chinese New Year, and a televised event, the New Year's Gala, similar to the United States' Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve (what a mouthful). On the whole, Chinese New Year is usually a much bigger celebration than the regular calendar New Year. Families, government officials, stores, airlines, and more all build up to the holiday with decorations, speeches, and special merchandise.

In celebration of Chinese New Year, here are some common Chinese phrases or terms you may use during the holiday:

As you may have noticed, my blog posts are usually rather lengthy...that's because I have a lot of ideas throughout the week, and I save them up to write in one cumulative blog post. I've seen some of my friends do these types of posts, so I'm going to start a specific category for all my rambling, slightly off-topic, meandering thoughts. (Honestly, I'm so clever. I'm like...a Renaissance man...)

If you can read the title, you may have already guessed what this post is about. Chinese New Year starts tomorrow! This year is the year of the sheep (羊). I say "starts" because Chinese New Year is a large celebration in China, lasting about two weeks. People get time off from work and school to celebrate with their families. In fact, some call this time of year the world's largest "human migration" because so many people take public transportation or fly home to celebrate. You may also lion parades at the beginning of Chinese New Year, and a televised event, the New Year's Gala, similar to the United States' Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve (what a mouthful). On the whole, Chinese New Year is usually a much bigger celebration than the regular calendar New Year. Families, government officials, stores, airlines, and more all build up to the holiday with decorations, speeches, and special merchandise.

If you can read the title, you may have already guessed what this post is about. Chinese New Year starts tomorrow! This year is the year of the sheep (羊). I say "starts" because Chinese New Year is a large celebration in China, lasting about two weeks. People get time off from work and school to celebrate with their families. In fact, some call this time of year the world's largest "human migration" because so many people take public transportation or fly home to celebrate. You may also lion parades at the beginning of Chinese New Year, and a televised event, the New Year's Gala, similar to the United States' Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve (what a mouthful). On the whole, Chinese New Year is usually a much bigger celebration than the regular calendar New Year. Families, government officials, stores, airlines, and more all build up to the holiday with decorations, speeches, and special merchandise.  |

| A woman hands a red envelope to a lion dancer |

|

| The Chinese Zodiac |

- 新年快乐 - (xīnnián kuàilè) happy new year!

- 恭喜发财 - (gōngxǐ fācái) another way to say happy new year. It's often written as gong hay fat choy, which is the Cantonese pronunciation. I'll have more coming about the different dialects of Chinese in a later post.

- 羊 - (yáng) sheep. The "years" are based off of the Chinese zodiac, which you can read more about here.

- 红包 - (hóngbāo) red envelope. Parents and grandparents often give brand new money, packaged in red envelopes, to younger children. (This was a good source of income in my childhood years. Oh to be young.)

- 身体健康 - (shēntǐ jiànkāng) good health to you - while the regular New Year's celebration in America is typically just a fun celebration (maybe with a few resolutions involved), Chinese New Year traditionally places a lot of emphasis on values like health, good fortune, and prosperity.

|

| (There were so many gorgeous New Year graphics. Here's the cutest!) |

Monday, February 16, 2015

Update 1: Let's Get Down to Business

The Formalities

In my last post, I gave you a preview of which topics I'd discuss each week, but I'd like to change that. The new schedule is below:

If you know me in real life, you may understand that I am...quite the organizer. Ever since I witnessed Pepper Potts in the Iron Man movies, I told myself I could be a personal assistant, if all else failed. Anyway, I knew I would need plenty of papers and flash cards for this project, so I dedicated a folder to it. It's my baby, and it's beautiful. You can see it below. In the upper left is my progress tracker. Every day I work on my project, I color in a progress bar. (I'm very extrinsically motivated - it was either this, or stickers.) Then, on the right, I have my flashcards binder-clipped to the folder. In this first week, the binder clip was already straining, so I'm going to have to swap this out every week. On the lower left is my little calendar. I've planned out when I need to finish each set of 50 characters, as well as when I'm going to start working on my TEDtalk. Also, I cross off each day we get closer to the final product. Then, on the lower right is one of my favorite motivational quotes. I can't honestly justify the amount of time I spent making it, but it makes me happy every time I open the folder.

Let's Get Down to Business...

I had a pretty straightforward process for learning the first fifty characters. First, I would write out the phonetic spelling of each character (also known as pinyin, which I'll be covering later), complete with the tones (also coming later). Because I know how to speak Chinese, this was my way of "translating". I was associating the written words with the spoken words I already knew. Then, I would practice writing the actual character. As you can see in the practice sheets, there are multiple spaces, where I would repeat the character over and over again. I realized halfway through that perhaps those spaces were for stroke order - which leads me to the topic of the week.

Stroke Order

I mentioned in last week's post that Chinese was a pictorial language. Each character is, in simplest terms, a picture. Let's look at a picture of a house, shall we?

To draw this house, one could go about it many ways. You could start with the basic outline and then fill in the details. Or you could draw the doors and windows first and then add the outline. You could draw from the ground up, or the sky down. If you wanted to start on the right side and continue to the left, or vice versa, you could. This house is a picture, and Chinese is made up of pictures. Like you could draw a house different ways, you could write Chinese characters different ways, right? No. (Why would Chinese ever be that easy? Silly reader.)

Like a house is made of straight lines, diagonal lines, curves, and dots, Chinese characters are made of different strokes. There are many different types of strokes, but here are the basics:

These are essentially the basic components that structure each character. These strokes have to be written in a certain direction (as the chart shows). For example, let's say you wanted to write a héng, a horizontal stroke. You can only write this stroke from left to right, never right to left. Building on this idea, each Chinese character is written with the strokes in a specific order. Again, these can never be written in a different order. In the end, you could produce the same result, if you used a different order. But a standard stroke order is actually more conducive to memorizing characters and also produces a certain aesthetic look. The rules for stroke order are as follows:

Back to Business

Returning back to my actual process of learning, I remembered most of these stroke order rules from my early days inhell Chinese school. In the instance that I didn't remember, the website chinese-tools was helpful in providing stroke order. Additionally, the website also has English-Chinese translations and vice versa. Finally, although every language teacher is clutching their chest in pain, Google Translate was also pretty helpful. The app on my phone has an option where I can just write the character - a much simpler method than googling pinyin or switching between various keyboards on my phone/computer.

I also promised that I would write a few practice sentences in Chinese, and here they are! Translations:

I was surprised with how much I could actually write. I take German at school, and it took me years to construct sentences like #3 or #5. As I was writing these, I was reminded of both the complexity and simplicity of Chinese. You may notice that I repeat a certain character in many of these sentences - 的(de). In English, one could translate this to "of". Interestingly, Chinese has no possessive case. In English, we can "my teacher's book" or "Julia's house". A literal translation of the same phrase in Chinese would be "teacher of book" or "Julia of house". This construction is called genitive case (and it's used a lot in German, less so in English). Although it may seem strange to English speakers, use of "de" for genitive in Chinese makes writing easiser. I didn't learn genitive case until two years into German. Another interesting thing to note: the spoken word "ta" in Chinese means both "he" and "she". However, the written word distinguishes between the two. This is why some Chinese speakers confuse "he" and "she"! (Also, as I learn Chinese, I lament more and more the lack of 2nd person plural in English. It seems common in other languages, so what happened to English?) The last thing I wanted to address was the specifics of familial terms. If you look at sentences #3 and #6, I refer to a "brother" in both. However, I used completely different words. In Chinese, one distinguishes between an older brother (哥哥) and a younger brother (弟弟). This applies to sisters, as well. In fact, Chinese has so many different terms for family members - we distinguish between older/younger and paternal/maternal.

I'm sorry this post got so long. It seems I have a habit of writing long blog posts. Last year, I would reward readers with cat gifs for sticking through long posts...maybe I should continue the tradition? (This is a vine, not a gif, but it's worth it)

- Jess

Resources

In my last post, I gave you a preview of which topics I'd discuss each week, but I'd like to change that. The new schedule is below:

Week 1: Building blocks- Week 2: Stroke order

- Week 3: Radicals

- Week 4: Simplified/Traditional

- Week 5: Pinyin

- Week 6: Dialects

If you know me in real life, you may understand that I am...quite the organizer. Ever since I witnessed Pepper Potts in the Iron Man movies, I told myself I could be a personal assistant, if all else failed. Anyway, I knew I would need plenty of papers and flash cards for this project, so I dedicated a folder to it. It's my baby, and it's beautiful. You can see it below. In the upper left is my progress tracker. Every day I work on my project, I color in a progress bar. (I'm very extrinsically motivated - it was either this, or stickers.) Then, on the right, I have my flashcards binder-clipped to the folder. In this first week, the binder clip was already straining, so I'm going to have to swap this out every week. On the lower left is my little calendar. I've planned out when I need to finish each set of 50 characters, as well as when I'm going to start working on my TEDtalk. Also, I cross off each day we get closer to the final product. Then, on the lower right is one of my favorite motivational quotes. I can't honestly justify the amount of time I spent making it, but it makes me happy every time I open the folder.

Let's Get Down to Business...

|

| 1/7 practice sheets from this week |

I had a pretty straightforward process for learning the first fifty characters. First, I would write out the phonetic spelling of each character (also known as pinyin, which I'll be covering later), complete with the tones (also coming later). Because I know how to speak Chinese, this was my way of "translating". I was associating the written words with the spoken words I already knew. Then, I would practice writing the actual character. As you can see in the practice sheets, there are multiple spaces, where I would repeat the character over and over again. I realized halfway through that perhaps those spaces were for stroke order - which leads me to the topic of the week.

Stroke Order

I mentioned in last week's post that Chinese was a pictorial language. Each character is, in simplest terms, a picture. Let's look at a picture of a house, shall we?

To draw this house, one could go about it many ways. You could start with the basic outline and then fill in the details. Or you could draw the doors and windows first and then add the outline. You could draw from the ground up, or the sky down. If you wanted to start on the right side and continue to the left, or vice versa, you could. This house is a picture, and Chinese is made up of pictures. Like you could draw a house different ways, you could write Chinese characters different ways, right? No. (Why would Chinese ever be that easy? Silly reader.)

Like a house is made of straight lines, diagonal lines, curves, and dots, Chinese characters are made of different strokes. There are many different types of strokes, but here are the basics:

These are essentially the basic components that structure each character. These strokes have to be written in a certain direction (as the chart shows). For example, let's say you wanted to write a héng, a horizontal stroke. You can only write this stroke from left to right, never right to left. Building on this idea, each Chinese character is written with the strokes in a specific order. Again, these can never be written in a different order. In the end, you could produce the same result, if you used a different order. But a standard stroke order is actually more conducive to memorizing characters and also produces a certain aesthetic look. The rules for stroke order are as follows:

- Top to bottom: components on the top are written before components on the bottom.

- Left to right: left-most components are written before components on the right.

- Horizontal before vertical: some characters are separated or "crossed" with horizontal or diagonal strokes. These horizontal strokes are written before vertical ones.

- Diagonals right-to-left before diagonals left-to-right: it was pretty simple before this one, right? Don't worry, it's a lot simpler in visual form. The character 人 (person) is written with two diagonal strokes. Both start at the top, in the center. One goes to the left, and the other goes to the right. The right-to-left diagonal stroke comes before the left-to-right.

- Outside before inside: some characters include components enclosed in others. The strokes on the outside go before the ones on the inside.

- Inside before bottom enclosing: an extension of the previous rule. If a component is enclosed in a character, it's written before the final enclosing stroke.

- Center verticals before outside "wings": some characters have outside "wings" that flank a center vertical stroke. These are written last.

- Cutting strokes last: some characters may have a vertical stroke that "cuts" through other components. these are written last.

- Left vertical before enclosing: again, with enclosing characters, the leftmost vertical stroke is written first.

- Top/upper-left dots first: pretty self-explanatory

- Inside/upper-right dots last: pretty self-explanatory

|

| Examples of the rules |

Returning back to my actual process of learning, I remembered most of these stroke order rules from my early days in

I also promised that I would write a few practice sentences in Chinese, and here they are! Translations:

- How are you?

- I am her mother.

- My brother's teacher is very good.

- Our guests drink tea.

- My father's Chinese book is mine.

- Little brother is not an adult.

- Thank you all.

- He is looking at the map.

I was surprised with how much I could actually write. I take German at school, and it took me years to construct sentences like #3 or #5. As I was writing these, I was reminded of both the complexity and simplicity of Chinese. You may notice that I repeat a certain character in many of these sentences - 的(de). In English, one could translate this to "of". Interestingly, Chinese has no possessive case. In English, we can "my teacher's book" or "Julia's house". A literal translation of the same phrase in Chinese would be "teacher of book" or "Julia of house". This construction is called genitive case (and it's used a lot in German, less so in English). Although it may seem strange to English speakers, use of "de" for genitive in Chinese makes writing easiser. I didn't learn genitive case until two years into German. Another interesting thing to note: the spoken word "ta" in Chinese means both "he" and "she". However, the written word distinguishes between the two. This is why some Chinese speakers confuse "he" and "she"! (Also, as I learn Chinese, I lament more and more the lack of 2nd person plural in English. It seems common in other languages, so what happened to English?) The last thing I wanted to address was the specifics of familial terms. If you look at sentences #3 and #6, I refer to a "brother" in both. However, I used completely different words. In Chinese, one distinguishes between an older brother (哥哥) and a younger brother (弟弟). This applies to sisters, as well. In fact, Chinese has so many different terms for family members - we distinguish between older/younger and paternal/maternal.

I'm sorry this post got so long. It seems I have a habit of writing long blog posts. Last year, I would reward readers with cat gifs for sticking through long posts...maybe I should continue the tradition? (This is a vine, not a gif, but it's worth it)

- Jess

Resources

- chinese-tools

- thechinesesymbol

- archchinese

- previous knowledge of English, German, and Chinese

Tuesday, February 10, 2015

Update 0: 大家好!

Hello everyone!

My name is Jess, and this blog is meant to document a six-week process through which I teach myself 300 Chinese characters - and, no, I don't regret this. Yet.

For those of you who don't know, I am Chinese. Luckily, I already have some background "native" knowledge in the language, which gives me an advantage over completely unfamiliar learners. That being said, I don't need to start at the most basic of building blocks - simple words like 大,小,火, 上,etc. These building blocks are useful, though. This is the theory the theory of one Chinese-learning website, Chineasy.

Building Blocks + Pictorials

Chineasy begins its Chinese lessons starting with its building blocks. These are simple characters that often appear in other characters. For example, this is the character for fire (huǒ)

And here is the character for flames (yàn). As you can see, it's a bunch of little "fires" stacked on top of each other.

Along with these bits of information, I will also be documenting my progress. These are the progress sheets I plan on using to practice writing. I'll scan a few of the sheets each week and upload them for you to see. Additionally, I plan on writing a few sentences to actually apply my knowledge (those will be uploaded too). I don't have specific goals regarding the characters, as they are difficult to divide into different "levels". Some are more complex to write than others, but they all correspond to certain words, and it takes the same amount of effort to learn and memorize them. As far as the sentences, I will only be looking into grammatical structure minimally, given that I already speak the language. I just hope that the sentences I write will eventually become more detailed/precise as I learn more words. My plan is to work up to the final product: a written recipe for scallion pancakes (and my TEDtalk may also feature the actual dish...). I'm also grateful for my family - I'm surrounded by native speakers who are probably more excited than I am that I'm finally taking the time to learn some Chinese.

I already have this week's practice worksheets printed out. Now I'm off to practiceand do English homework!

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Resources

My name is Jess, and this blog is meant to document a six-week process through which I teach myself 300 Chinese characters - and, no, I don't regret this. Yet.

|

| got Chinese? |

For those of you who don't know, I am Chinese. Luckily, I already have some background "native" knowledge in the language, which gives me an advantage over completely unfamiliar learners. That being said, I don't need to start at the most basic of building blocks - simple words like 大,小,火, 上,etc. These building blocks are useful, though. This is the theory the theory of one Chinese-learning website, Chineasy.

Building Blocks + Pictorials

Chineasy begins its Chinese lessons starting with its building blocks. These are simple characters that often appear in other characters. For example, this is the character for fire (huǒ)

|

| Building block for "fire" from Chineasy |

|

| "Flames" from Chineasy |

This makes it a little easier to learn some Chinese characters, but the visual cues can only tell you so much. If I didn't know the word above was "flames", I could guess that it was related to fire. Beyond that, I wouldn't be able to say. In English, the Latin alphabet gives speakers an advantage. The word "antidisestablishmentarianism" is a mouthful. But if speakers dissect the prefixes and suffixes, they know that it has to do with getting rid of something. Therefore, Chinese learners need to use rote memorization to learn most of their characters.

Motivation

So, we've established that reading and writing Chinese is a bit of a challenge. And I already know how to speak and understand the language so...why learn more? The truth is, I've always felt a little estranged from my family members. Growing up in America has forced me to reconcile two cultures that are sometimes completely incompatible - even the littlest things remind me that I'm not quite American. When I go over to a friend's house for dinner, I stop and consider whether I should take off my shoes, and then I eat a meal without a bowl of rice. Despite this, I speak English better than Chinese; I use a fork more often than chopsticks; and I dress in American clothing. As all my relatives in China say, I'm American - but not quite. Learning how to read and write Chinese will hopefully bring me closer to my family and culture. After all, I'd like to actually write a birthday card to my grandparents, or read a menu in Chinatown every now and then.

Measuring Achievement & Resources

Each week, my blog post will feature a different post about an aspect of the Chinese language:

- Week 1: Building blocks

- Week 2: Radicals

- Week 3: Simplified/Traditional

- Week 4: Pinyin & Tones

- Week 5: Dialects

- Week 6: None

|

| Scallion pancakes (葱油饼) - yum! |

Goal

When this project is over, I will have learned 300 Chinese characters. Additionally, I hope to write a recipe for scallion pancakes, or 葱油饼. But, most importantly, I will have a deeper connection to my family and culture. According to some, learning Chinese is a lifelong effort - the BBC estimates that the average Chinese person will know around 8,000 characters, and one needs 2,000 to 3,000 to read a newspaper article. Hopefully, this beginning will motivate me to continue my pursuit later.

I already have this week's practice worksheets printed out. Now I'm off to practice

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Resources

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)